The art of storing veneers

The production of veneer, like many industrial processes, is complex and a couple of straightforward Google searches will provide plenty of information on how the stuff is made. Essentially, the bark is stripped from the complete log which (depending on its eventual use) may then be cut or quartered. The next process is to soak the timber for anything up to 72 hours at a temperature of between 80-100°C; after which a sharp blade is held against the moving wood for one of several methods used to produce the veneer.

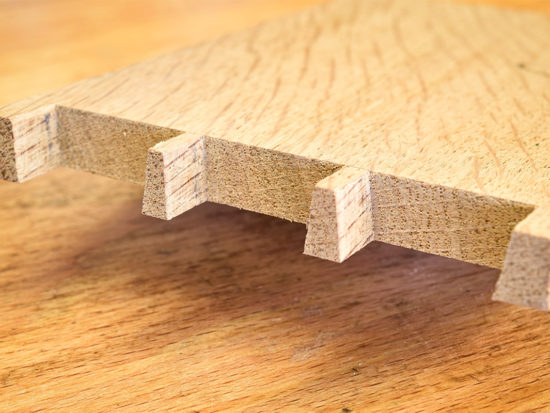

One way is to ‘unpeel’ the log to form one continuous sheet...rather like unravelling a roll of kitchen towelling. This method provides a huge, unbroken sheet of thin timber which is ideal for making plywood. Other methods of conversion produce different types of finished veneer: either straight grained or so called ‘crown’ cut with the familiar arched pattern in the grain. It’s only the best logs that are so converted, resulting in veneer of the highest quality which is then suitable for use in trade, furniture and cabinet making ‘shops.

From a practical point of view, it should be noted that to keep the grain pattern as a seamless match, great care is taken to see that each sheet of veneer is contiguous with the one preceding and the one after. The first thing that should be done in the workshop when opening a parcel of veneer is to mark clearly in chalk or dark, soft pencil the slicing order of the leaves. Once they’re mixed up, it’s almost impossible to sort them out again! This might not be too critical if the individual leaves are fairly bland, but it becomes important when the grain pattern shifts slightly from one leaf to the next throughout the parcel. Mixing them up makes it a lot harder to pattern match them later on so marking them at the outset is one of those things that has to be done automatically...neglect it at your peril!

The pic shows a pack of mahogany veneers, where the first four have been labelled 1-4 in sequence and it can be seen that the grain pattern shifts marginally from leaf to leaf. Commercial veneers are normally cut to 0.6mm thick (the approximate thickness of a cereal box) and are very, very fragile, so storage in the workshop could become a problem. By far the best method is to keep them between them two sheets of ply or hardboard, wrapped up with string and stored somewhere of harm’s way.

Over time, they also dry out and can become very brittle when handled. Unless the parcel and individual leaves are treated with ‘kid gloves’, it becomes very easy to end up with a load of split and mangled leaves which makes life a little bit harder, though not impossible, as I’ll explain next time when I’ll look at ways of cutting and matching thin commercial veneer.